At what point does a “trespasser” become a “squatter” from a legal perspective?

At what point does a “trespasser” become a “squatter” from a legal perspective?

If someone breaks into a vacant house or empty apartment and spends the night on the floor, they are clearly a trespasser. But what if that trespasser stays a week? A month? Or longer?

What if that person moves in furniture? Starts receiving mail there?

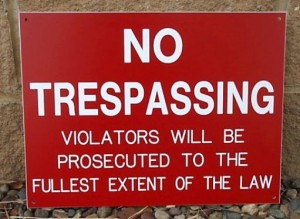

As a practical matter, there comes a time when the police will not intervene and will not return your real property to you without a court order. From a legal perspective, there is no difference between someone who breaks into your real property and stays one month versus one night. Both constitute acts of trespassing. Remember that police officers are not movers and will not carry boxes or lift furniture. So, catching and removing trespassers early is important.

With the mortgage foreclosure crisis lingering, these scenarios are real. There are thousands of reported cases across the nation involving persons or entire families moving into foreclosed and vacant properties. The home is owned by Family A (or the bank that lent money to Family A), but Family B moves in and literally “makes themselves at home.” There are cases where a family will move into a foreclosed home, is removed under court order, and then moves into the vacant home next door, across the street or down the road. With the number of foreclosures holding steady, this is likely to be a continuing problem.

In most states, there are separate definitions of civil versus criminal trespass.

Criminal Trespass is usually defined by a person who, not having a contractual interest in the real property at issue, knowingly or intentionally refuses to leave the property of another person after having been asked to leave by the other person or that person’s agent. Criminal trespass is usually a misdemeanor but can be a felony if the trespass occurs on government property, especially public school property.

Civil Trespass is generally defined as conduct amounting to a wrongful invasion of the property of another. In order to succeed on a civil trespass claim, a land owner must prove that (1) the owner was in possession of the land in question, and (2) the defendant entered the land without right. Then there is the issue of damages. Under English common law, real property rights were so important that many states still adhere to the old principle that an owner is entitled to nominal damages without any proof of actual injury, and, upon additional proof of injury or loss, to compensatory damages. In recent decades, some states have begun requiring intent and actual damages as additional elements that an owner must prove to maintain an action for civil trespass. Most states, however, define civil trespass as an intentional act of occupying someone else’s land without permission without regard to actual damages.

Exclusive Possession

In some states, a property owner must prove that he has exclusive possession of the property in dispute. In these states, there is often a question as to whether a landlord of a building with common areas utilized by many tenants and their guests can maintain a trespass action, because the landlord does not exclusively possess the common areas. Most states, including Indiana, have resolved this issue in favor of the landlord.

Adverse Possession

Lay people often talk about “squatter’s rights,” when describing a concept that lawyers and judges call “adverse possession.” The concept is actually a statute of limitations by which a property owner must sue a “squatter” before losing title of the property to the squatter. In most states, the statutory period necessary to achieve adverse possession is ten years, meaning the squatter has to use the disputed property as his own and often must pay taxes on the property before the original owner loses title. The elements necessary for a “squatter” to establish such a claim under adverse possession are:

- actual possession;

- which is visible;

- open and notorious;

- exclusive;

- under a claim of ownership;

- hostile to the record owner; and

- continuous for the statutory period.

Adverse possession cases are fact-sensitive and are decided on a case-by-case basis. Once a “squatter” has sustained his burden as to adverse possession, title to the disputed real property is acquired by operation of law and the original owner’s title is extinguished at that time.

Vacant Properties

The number of vacant properties, both single-family homes and multi-family apartments, has increased significantly in recent years during the “Housing Crisis.” Many states have sought a balance between respecting common law property rights and the needs of banks, community organizations and neighbors, the latter of whom often will mow weeds, board up buildings and do what they can to prevent abandoned homes from turning neighborhoods into areas of plight. Some states now allow non-owners to enter a property, with immunity from civil lawsuits, if they believe it is vacant, to do minor maintenance, lawn care, boarding, etc.